Groundbreaking project corrects faulty DNA linked to fatal heart condition and raises hopes for parents who risk passing on genetic diseases

A human egg seen through a microscope. In the study, Crispr-Cas9 was used to fix mutations which cause a potentially fatal heart condition known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Photograph: Getty Images

A human egg seen through a microscope. In the study, Crispr-Cas9 was used to fix mutations which cause a potentially fatal heart condition known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Photograph: Getty Images

Ian Sample Science editor

Scientists have modified human embryos to remove genetic mutations that cause heart failure in otherwise healthy young people in a landmark demonstration of the controversial procedure.

It is the first time that human embryos have had their genomes edited outside China, where researchers have performed a handful of small studies to see whether the approach could prevent inherited diseases from being passed on from one generation to the next.

While none of the research so far has created babies from modified embryos, a move that would be illegal in many countries, the work represents a milestone in scientists’ efforts to master the technique and brings the prospect of human clinical trials one step closer.

The work focused on an inherited form of heart disease, but scientists believe the same approach could work for other conditions caused by single gene mutations, such as cystic fibrosis and certain kinds of breast cancer.

“This embryo gene correction method, if proven safe, can potentially be used to prevent transmission of genetic disease to future generations,” said Paula Amato, a fertility specialist involved in the US-Korean study at Oregon Health and Science University.

The scientists used a powerful gene editing tool called Crispr-Cas9 to fix mutations in embryos made with the sperm of a man who inherited a heart condition known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM. The disease, which leads to a thickening of the heart’s muscular wall, affects one in 500 people and is a common cause of sudden cardiac arrest in young people.

Humans have two copies of every gene, but some diseases are caused by a mutation in only one of the copies. For the study, the scientists recruited a man who carried a single mutant copy of a gene called MYBPC3 which causes HCM.

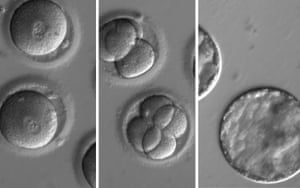

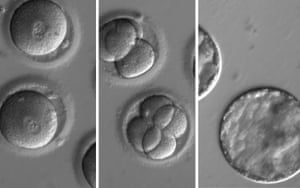

FacebookTwitterPinterest This sequence of images shows the development of embryos after injection of a gene-correcting enzyme and sperm from a donor with a genetic mutation known to cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Photograph: (OHSU)/OHSY

When the scientists made embryos with the man’s sperm and healthy eggs from donors, they found that, as expected, about half of the embryos carried the mutant gene. If the affected embryos were implanted into women and carried to term, the resulting children would inherit the heart condition.

Writing in the journal Nature, the researchers describe how gene editing dramatically reduced the number of embryos that carried the dangerous mutation. When performed early enough, at the same time as fertilisation, 42 out of 58 embryos, or 72%, were found to be free of the disease-causing mutation.

The work has impressed other scientists in the field because in previous experiments, gene editing has worked only partially, mending harmful mutations in some cells, but not others. Another problem happens when the wrong genes are modified by mistake, but in the latest work the scientists found no evidence of these so-called “off target effects”

“They’ve got remarkably good results, it’s a big advance.” said Richard Hynes, a geneticist at MIT who this year co-chaired a major report on human genome editing for the US National Academy of Sciences (NAS). “This brings it closer to clinic, but there’s still a lot of work to do.”

Read more

Today, people who carry certain genetic diseases can opt for IVF and have their embryos screened for harmful mutations. The procedure can only help if there is a chance that some embryos will be healthy. According to Shoukhrat Mitalipov, who led the latest research, gene editing could bolster the number of healthy embryos available for doctors to implant.

More work is needed to prove that gene editing would be safe to do in people, but even if it seems safe, scientists face major regulatory hurdles before clinical trials could start. In the US, Congress has barred the Food and Drug Administration from even considering human trials with edited embryos, while in the UK it is illegal to implant genetically modified embryos in women. The procedure is controversial because genetic modifications made to an embryo affect not only the child it becomes but future generations too. “It’s still a long road ahead,” said Mitalipov. “It’s unclear when we’d be allowed to move on.”

In the latest study, the mutation was corrected by a route that scientists have not seen before, with the cell copying healthy DNA from the mother’s egg instead of the template. One question scientists need to explore now is whether mutations carried by eggs can be corrected as easily as those carried by sperm.

“If all of this holds up for different genes and is also true when the mutation is inherited from the mother, it will be a major step forward,” said Janet Rossant, senior scientist and chief of research emeritus at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

Asked about the potential for gene editing to produce designer babies, Rossant, a co-author of the NAS report on gene editing, said it was a distant prospect. “We are still a long way from serious consideration of using gene editing to enhance traits in babies,” she said. “We don’t understand the genetic basis of many of the human traits that might be targets for enhancement. Even if we did, a genetic alteration that enhanced one trait could have unexpected negative consequences on other traits, and this would be an inherited feature for the next generation.”

“The NAS report came out strongly against any form of gene editing designed to simply enhance human potential,” she added.

No comments:

Post a Comment